Recent Update: I was asked to give this presentation at the 2022 Game-Based Learning Conference, which you can see a recording of below.

Love teaching? Love games? Ever wanted to bring the magic of learning into the magic circle of a game, or bring the magic of a game into the classroom? Me too.

That’s why I create educational board games. There’s a lot you can learn from games, but it’s not easy to fully develop a game, and as a teacher we need games that teach our curriculum.

That’s why I have been hard at work experimenting with games that are more open and have fewer rules. I have had a lot of successful experiments ranging in everything from a megagame for up to 72 players to card games for 2-5 players. The strategy games I’ve created teach their key objectives really well, but they took a long time to develop. Full game development is not something I have time to do for every lesson and key learning objective.

Students playing our World Leader Political Science Megagame “ALLIANCE”

But what if we could take a typical lecture and make a couple tweaks to make it feel like a game? Actually, we can. And I’m not just talking about making a Kahoot quiz game, although it can be just as easy.

All you need to turn a lecture into a game is a scenario that leads to a difficult choice. That’s it.

As a matter of fact, if you can center your lecture around one well designed multiple choice question, then you have yourself all the benefits of game based learning.

This can work well for any lesson, but my favorite way to use it is for English literature and history lessons–two of my favorite subjects. I just finished watching a YouTube lecture series called, “Shakespeare & Politics,” taught by professor Paul Cantor at Harvard, and I recently wrote 4 articles which I also turned into podcast episodes, so let’s see if we can turn Shakespeare’s King Henry V into a game based lesson.

The first thing we need is one well designed question.

For this lesson we will try to reduce the lesson into a multiple choice question, assuming we want to finish the lesson within one class period.

If you have not read Shakespeare’s King Henry V don’t worry. It is available on https://www.sparknotes.com/shakespeare/henryv/ and it has recently been made into a really great film called, “The King,” on Netflix featuring Timothy Chalomet. These two versions don’t match up perfectly, but for our purposes they are close enough.

This works for almost any pivotal moment from any historical event or story, because ultimately history is made up mostly of characters with great power, at pivotal moments, with limited information, who have to make difficult choices with critical outcomes for their people groups. This is true for both protagonists and famous historical political leaders. It’s what makes stories worth telling. These are the case studies we love to learn from.

Let’s come up with a list of interesting questions to explore. Any one of these could become the centerpiece of the lesson. Think about your learning objectives when choosing a good question.

Shakespeare related Questions

- What philosophical and political theories was Shakespeare exploring by writing this play?

- What makes a good king?

- Does Shakespeare believe like Machiavelli that a successful king must be willing to resort to unethical tactics to achieve a peaceful reign (the ends justify the means)?

What critical choices did King Henry V himself have to make?

- If you became king at a young age, which of these strategies do you think would help to establish yourself as a powerful ruler and earn the people’s respect?

- How would you have treated your friends, like Sir John Falstaff, after becoming king?

- If you were king at his time would you have tried to take France for yourself?

- Would you have retreated if you were outnumbered at Agincourt?

- If you had won the battle of Agincourt what would you have done with the enemy’s soldiers?

Start with one but you could actually go from one to another sequentially if you wanted to. But using even just one according to the rules I am about to establish will make your lecture far more engaging.

For our example let’s imagine we are teaching political science and want to choose the question that would best connect with other great works of literature like Shakespeare’s other plays or Machiavelli’s the Prince. To fully develop the question we will probably end up combining some of the questions or working some of them into the multiple choice answers.

Leading Question: If you became king at a young age, which of these strategies would you employ to earn the people’s respect?

This will allow us to incorporate some of the smaller choices that King Hal made into the multiple choice answers, and possibly even some of the strategies suggested by Machiavelli. But this is just my rough draft or first idea. As we start developing the lesson the initial question is likely to change.

The Principles of Game-Based Lecturing

The principles for making this work are as follows. I will explain each in detail later on.

- Hidest thy truth in the exposition (foreshadowing)

- Be wary of spoilers.

- Each choice must appear most valid

Rule # 1 – Hidest thy truth in the exposition (foreshadowing)

Exposition is the contextual details needed for your audience to understand what’s going on. It’s the back story of the characters, the time period, the setting, the circumstances, and/or the previously established relationships that will weigh in on the difficult choice that must be made.

Great writers often have to find creative ways to convey this information in an entertaining way. Teachers, especially teachers passionate about their subject, typically find details more interesting than most people, but don’t give too much information. We always know more in hindsight, but don’t let the audience know any more than the protagonist would have known at the time. Limited intel creates dramatic tension.

Give contextual details that will

- help flesh out the characters in the story

- Show how high the stakes of this decision are for the protagonist and those he/she leads.

- Help the audience to share the biases of this particular people

- Create a limited perspective

(Optional) Foreshadowing

Now for those of you who want to reach the advanced level. If there is a moral to this story that you want to reveal at the end of the lesson, you should plant the seeds for it in the early most boring part of your setup before you get to the critical question.

For our example we could actually watch a few key scenes from the Netflix film, “The King,” with the audience or watch it up to the midpoint crisis and then pause the film, and pose your question.

To make this as easy as possible, and to get the most out of the resources available to us in the shortest amount of time, let’s show this trailer for our example to establish the context in a fun dramatic fashion.

Sneak in some Philosophy

If I want to give a really deep lecture about leadership, I would sneak in some philosophical ideas about political rule introduced by Socrates in Plato’s Republic, Aristotle’s ideas in his books on Politics, or Machiavelli’s ideas in The Prince. At the conclusion of the lesson I would come back to these ideas and show how they apply to the decisions King Henry had to make.

Rule # 2 – Be Wary of Spoilers

In the case of history we often already know the ending, or if we don’t we can certainly find out. For instance, someone in the room is going to know that ultimately some of those Roman senators did in fact decide to assassinate Julius Caesar. No surprise there. But this is only the case with the most famous parts of the most famous stories. You can easily resort to the less popular moments, center on lesser known characters, or avoid the use of famous names of people and places only to reveal them at the end after the conclusion is given.

You also must be careful not to accidentally explicitly tell or unconsciously signal to the audience what the answer is. This is especially the case if you are doing this on the fly or half haphazardly. Remember students are professional multiple choice question test takers.

Another approach is to word the question so that it is more about what each individual in the audience would have done, instead of focusing on what the actual protagonist chose to do. For example, instead of asking the obvious, “what do you think King Henry did when faced with this choice,” you can ask, “knowing the kind of person you are, which of these options do you think would most appeal to you?”

Rule # 3 – Each choice must appear most valid

This is where preparing your lecture will begin to feel like developing a game. You may have to create multiple iterations of the question and each answer to get this right. Time spent here is time well spent. Let’s dive right into our example.

Q: If you became king at a young age, which of these strategies do you think would help to establish yourself as a powerful ruler and earn the people’s respect?

This is too long and can easily be shortened to

Q: If you became king at a young age, which of these strategies would you employ to earn the people’s respect?

Now I’ll just throw out a bunch of the strategies King Hal actually employed and then re-write them to make them look like options available to our young newly appointed audience rulers who are now each individually on the hypothetical throne. These are mostly in chronological order.

- Hal avoided the throne and mingled with soldiers and peasants in bars and brothels while his father, King Henry IV ruled at court.

- Hal put down the rebellion of his archrival, Hotspur (Henry Percy), by defeating him in one on one battle.

- King Henry V, known as Hal to his old drinking buddies, banished the beloved Sir John Falstaff to gain respect from those who were formerly his friends.

- King Henry V didn’t know whether or not to take offense at the dauphin’s gift.

- King Henry V, with a somewhat valid claim to the French throne, offended by a gift from the French, and encouraged by advisors he didn’t fully trust, decided to invade France

- King Henry V made a behind-closed-doors deal with the church to get them to introduce the idea of invading France (very Machieavellian method)

- The dauphin disrespects, deeply offends King Henry, and murders innocent English children.

- King Henry V, upon finding out that his invading army is outmatched by 5 to 1 by the French, offers to fight the Dauphin in one on one battle. The request is rejected, “Are you scared King Henry?… Surrender to me, now!”

- Despite the odds being against him, King Henry V fought using an extremely risky strategy. The gamble paid off and they won the war. The dauphin is killed leaving the French throne without an heir.

- King Henry V agrees to marry the princess of France. Their child will be heir to both the throne of England and France.

Plays, fictions, and well structured narratives, and especially Shakespearian plays, often build up to a midpoint crisis. The obstacle the protagonist must face and the decisions about how to do so at this point in the story are the easiest to build your lesson around. In our story the battle of Agincourt ends up being the climactic crisis. If we were to center on this then the question would be something like

Q: In King Henry’s position which strategy would you employ?

- a) Accept the French King Charles’ concessions and retreat.

- b) Refuse the concessions and continue to battle employing an extremely risky strategy.

- c) Offer to settle the war in a one on one duel with the Dauphin.

You’re Done – The Rest is Just for Fun

This is basically good enough. It will already make your lecture far more engaging than just telling everyone matter of factly what happened in the story detail by detail, date by date, name by name.

Audience Engagement

But we can make it much more nuanced and game like if we want. This works for any audience since we are treating everyone as an individual and allowing them to make their own choice, but if we have a large audience we might as well take advantage by allowing for input and making it visual to everyone else.

The first way we can do this is by allowing the audience to submit their own alternative clever creative choice. For mature audiences, encourage them to introduce a Machiavellian scheme, perhaps one that plays one stakeholder against another, or back door dealing. If someone has one to offer then add it to the presentation, white board, or display.

Q: In King Henry’s position which strategy would you employ?

- A) Accept the French King Charles’ concessions and retreat.

- B) Refuse the concessions and continue to battle employing an extremely risky strategy.

- C) Offer to settle the war in a one on one duel with the Dauphin.

- D) Other: An audience member may offer up their own alternative option for everyone to consider, preferably a clever creative Machiavellian strategy

Sli.do

For extremely large audiences it would be fun to use something like sli.do, a webapp that allows your audience to engage in the questions. There may be alternative webapps but this is the one I know of and it has all the features I was looking for when I found it. It provides engaging presentation tools that allow audience members to participate in live polls and ask questions. Audience members can answer each other’s questions, and upvote the questions so that the most popular questions rise to the top. For our purposes we can use an open ended question to accept suggestions for an alternative option to be considered by the audience, and we can then use a live poll to see which strategy they choose to employ and show the results in real time!

If you go this route I suggest you have an assistant with a laptop to sort through and manage the audience engagement so that you can focus on speaking. You can simply present the questions, and then later when you are ready, ask your assistant to show and share a summary of the audience’s feedback.

Designing your answers

To make this work well you may have to write, re-write, and reorder your list of possible answers. You may need to remind the audience of what is at stake. Go over the pros, cons, and give them simple labels to highlight their differences. But every aspect will be a signal to the audience. Even the order in which you present the options could affect which choice they lean towards.

To make it more engaging you will design it so that each option seems like the best answer but for a different reason. You don’t have to make these labels visible, you can just tell them to the audience as you explain each option’s pros and cons.

Q: In King Henry’s position which strategy would you employ?

- A) Accept the French King Charles’ concessions and retreat. Safe Option

- B) Refuse the concessions and continue to battle employing an High Risk/High Reward

- C) Offer to settle the war in a one on one duel with the Dauphin. Extreme Personal Risk

- D) Other: An audience member may offer up their own alternative option for everyone to consider, preferably a clever creative Machiavellian strategy

BALANCING OUT THE OPTIONS IS CRUCIAL

You can provide critical contextual details that reference

- military strategy,

- environmental circumstances,

- time period technology,

- army size,

- limited intel,

- personal biases,

- character flaws,

- motivations,

- short and longterm considerations,

Anything that should weigh in on their decision.

You should add or omit these contextual details as well as pros and cons to lend more credibility to what would otherwise look like a weaker option.

Game Mechanisms

We might not typically think of voting as a game mechanism, but by nearly every definition of games, voting turns your lecture into a game. I will also introduce some other game mechanisms aka mechanics, but the easiest, most common, and effective tool for audience engagement is voting.

Make the vote results visible.

Use a live poll if you have a good wifi connection and a good projection setup. If you have a whiteboard then have audience members give a show of hands and write the number of votes or percentage next to each multiple choice option. Do not underestimate just how rewarding it is for each audience member to see their choices affect the presentation!

This work, and it is work, can be allocated to a trusted assistant. For example they could pass out a pen and note card to each audience member, then after you label each choice, they can write down their vote anonymously. After the assistant collects the notecards and tallies up the votes either you or the assistant can present the results.

We can also use different voting systems to make it even more nuanced. For instance you could allow each participant to have multiple votes and spread them across multiple choices, or put in all their votes for their favorite option lending it more weight.

You could give a sticker, or multiple stickers to each participant and allow them to come up to the screen or whiteboard to place their votes next to the options they prefer.

Simulating Political Power, Privilege, & Class Systems with Alternative Voting Systems

You could give special stickers to a privileged category of participants that count more than other votes. This is great for roleplaying or acknowledging when certain decision makers have more skin in the game or more expertise. It can also simulate the powerful upper classes found in most ancient political societies.

You could also use different styles of stickers with equal weight to simulate political parties or factions. This way you can see who if anyone is crossing party lines.

It’s also fun to let one participant come up to the stage to roleplay as the ruler. This final decision maker votes last, and only his/her vote counts! But they will of course have to justify themselves if they go against the majority. Can you feel the dramatic tension?

Rank order voting is in my opinion the most considerate elaborate voting system, but it is also probably the least popular. I would encourage you to research it if you are interested in fair and creative systems.

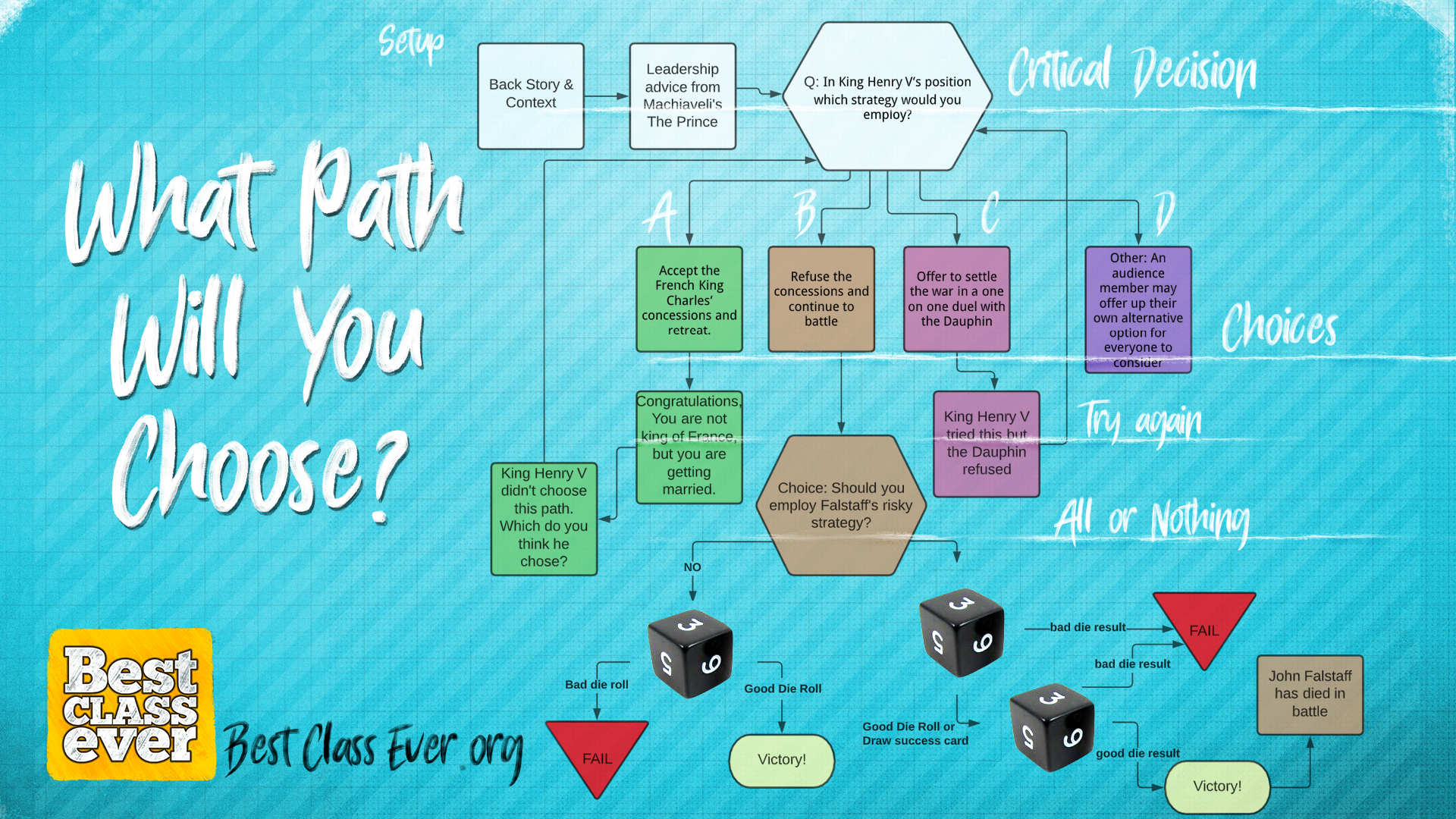

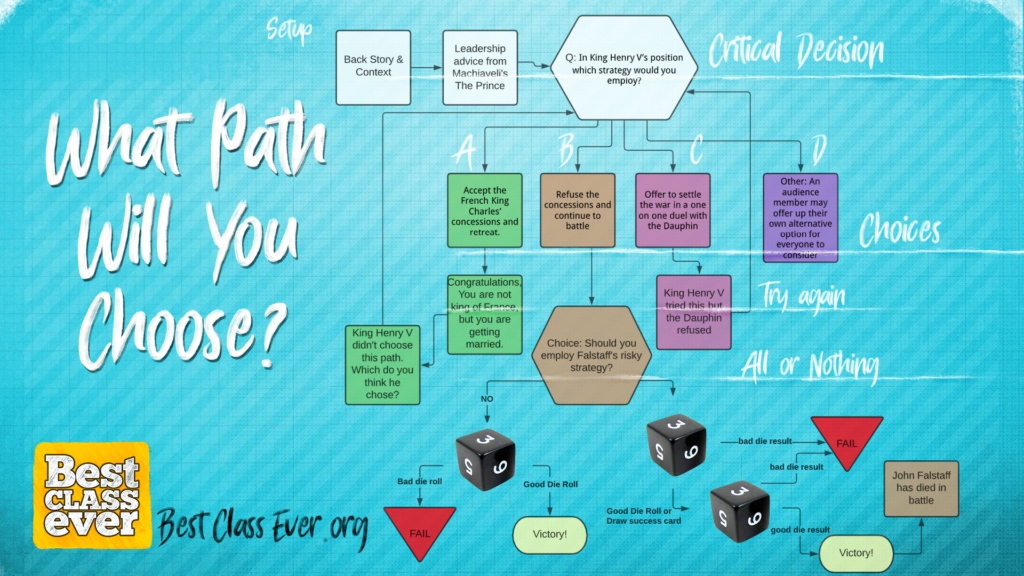

Choose Your Own Adventure

The next best way to gamify your lecture is to create a flow chart of the different consequences. This allows your initial choice to lead into other more nuanced choices down the road, much like a choose-your-own-adventure. I created a flow chart for our example which you can see at the end of this article.

After you have collected the votes and made them public, you would then need to explain the results of each option.

Let’s dive right into our example. In King Henry’s choice concerning the battle of Agincourt we would have the following consequences starting with the first multiple choice option.

The Safe Option

Context: When King Henry V arrived in Harfleur with a large fleet of warships King Charles was surprised. So King Charles of France offered a compromise. He would not give Henry the crown of France, but he would give him some small dukedoms—that is, small sub-regions within France—as well as the hand of his daughter, Catherine, in marriage if King Henry V agreed to leave France peacefully.

Consequence: King Henry V didn’t choose this option, so we could explain that he had risked a lot to get this far, and most of those risks had paid off. So it would seem reasonable for him not to settle for the compromise offered by King Charles of France.

So now we can eliminate the first multiple choice option and vote again or simply explain the consequences of the next multiple choice option.

Extreme Personal Risk Option

Context: After sweeping through France with multiple victories, and a successful siege of Harfleur, King Henry V found his army outnumbered five to one at Agincourt. He offered to settle the war in a one-on-one duel with the King’s son known as the Dauphin in French. He argued that it would save many Christian soldiers from having to spill their blood. King Henry V had successfuly put down Hotspur’s rebellion using this same strategy, so it made sense for him to try it once again here. It put him at great personal risk, but it was not nearly as risky as going into all out battle when his men were outnumbered. This would remove the Dauphin’s advantage.

Consequence: The Dauphin rejected the offer and demanded King Henry’s surrender. France had been humiliated by this young king’s invasion, and the young King Henry was insulted by the Dauphin’s treatment.

So we can now eliminate this strategy from the list of available options as well. At this point he must either retreat or go to war.

You might have noticed that I skipped the second option and jumped directly to the third. My order was intended to make the actual historical sequence of events a little less obvious.

This is now a binary choice. He may either retreat or go to war with the odds against him. If you have the time and the patience, this might be a good time to let the audience vote again. If you do I would emphasize that if he retreats at this point King Charles’ may want to re-negotiate the compromise and be far less generous this time.

High Risk High Reward Option

Always have a high risk high reward option. It’s like doubling down in gambling, or pushing your luck in Black Jack. There’s nothing more fun than raising the stakes.

Context: As we already mentioned, King Henry V is both outnumbered five to one and he is an invading force. The invading force is always at a disadvantage militarily because

- The invading force doesn’t know the terrain as well

- Operating far from home is expensive and dangerous because resupply lines must be kept secure

- The enemy will fiercely defend their homes because they have much to lose

- The enemy can retreat to familiar territory and easily prolong the war until they have even more advantage

King Henry’s advisors suggested he negotiate even if he lost the upperhand. They all agreed except Sir John Falstaff.

Falstaff offers an extremely risky military strategy. He believes it will rain, and if it does then the men could gain the advantage by wearing light armor. But they will have to lead with a small heavily armored division as a decoy to hide their intentions. Then, assuming the Dauphin would commit the bulk of his forces, the light infantry would then have to fight in the mud. The hope here is that their advantage in maneuverability would outweigh the French advantage in numbers.

Consequence: Historically we know that King Henry V did not back down and ultimately won the battle of Agincourt. But he made his decision not knowing what the result would be and hopefully, if you have done your job well, your audience will have to make the choice not knowing this either. So don’t reveal any of these facts until after they have committed to a decision.

To really make this feel like a board game, we can use dice or shuffled index cards to simulate all of these risks. It’s still fun even if you don’t go this far, so it depends on how much interest you have in mathematical probabilities and nerd culture.

Simulating Risk with Dice and/or Index Cards

This requires some simple math probabilities and either dice, index cards, or a random number generator aka RNG (simply type “RNG” into Google).

The advantage of dice.

Dice create an atmosphere of fun because they are so closely associated with board games and gambling.

In case you’ve never played Dungeons & Dragons, any other Tabletop RPG, or are completely unfamiliar with wargaming, the way you would simulate a battle in which one army is outmatched five to one, is you would roll a six-sided dice (also known as 1 6D) and to win the battle the player would need to roll a 6. For 3:5 odds the player would roll 1 10D (a ten-sided dice) and need a result of 6 or greater to succeed.

Mathematically speaking, rolling one die is truly random. Human beings are terrible at intuitively understanding probabilities so this can be problematic. For this reason game designers typically prefer using shuffled cards to help reduce the amount of randomness.

Using two six-sided dice (2 6D) has a higher probability of getting a mid range result which is sometimes preferred since it more closely simulates the typical normal distribution or regression to the mean.

Throwing dice feels and sounds incredible. The participant has an incredible amount of control over the dexterity of throwing the dice, but the result is still completely random. There is no rational correlation between how the person throws the dice and the result. Yet we still love to blame or give credit to the participant for their perceived luck.

The Advantage of Index Cards

You can write a result on each card. To increase the odds of a result you can simply make duplicates of that card. This allows us to directly control the probabilities. We can also add stats, narrative details which game designers call, “fluff,” and add additional rules or mechanics to each card if you want to make the game even more nuanced. You could also add bonus rewards to each card or visuals like photos, illustrations, or icons. We could number the cards or add color and typography to differentiate them.

Just make sure they all look identical on one side so you can shuffle them.

We can also reduce the randomness with each turn by removing cards each round. It’s nearly impossible to reduce the randomness of dice rolls.

To simulate the advantage of the French having 5 times more troops for example, we could write, “Victory,” on 1 index card, write, “FAIL” on 5 index cards, shuffle, and then draw 1 card.

A typical poker deck can also be useful.

Simply reduce the deck down to the cards needed and explain to the audience which aspects of the cards represent what. For example, drawing a black card could mean one thing, and drawing a red card could mean another. You could assign meaning to the suit, or see who draws the highest number. Players could be assigned roles based on which royalty card they draw, etc.

To Simulate King Henry V’s predicament I would use a series of card draws to simulate the series of choices that need to be made.

First, let’s simulate the choice to use Falstaff’s risky strategy or not. If not then the odds that they will win are weighted 5:1 in the enemy’s favor. Simply write victory on one card, and Fail on 5 cards. Shuffle and Draw one card.

Second, let’s simulate Falstaff’s strategy. We are simulating both the chance that it will rain, and then the chance that the Dauphin will commit his troops and fall for the trap. It’s debatable what the probabilities should be, but both conditions would need to be satisfied for King Henry V to win the war. A fail on the first draw would be a complete failure without going to the second draw. A fail on the second draw would also be a complete fail. So maybe you should go easy on the odds for each draw since the combination of them will dramatically increase the odds of ultimate failure. We could also weight the results in favor of success since that is what the historical result was, but again these probabilities come down to your discretion. Your choice will have strong philosophical implications about how much you believe in fate, predeterminism, and randomness.

Surprise Event Deck

Even if you choose to use Dice or digital RNG, it might still be fun to write some random surprise events on index cards and shuffle them into a deck to draw from. Things rarely go according to plan, weather was far less predictable before the science of meteorology, and it is impossible to know for certain how rational human behavior will be. All of these delightful surprises can be written onto cards and drawn randomly to simulate uncertainty. Ideally some cards will raise the stakes, some will cause an unexpected setback, and some could give a small bonus. They could provide intel or contextual details to help flesh out the reality of the situation. According to the principles of good game design they could reduce or increase uncertainty, but none of them should provide absolute certainty or remove agency from the participants. We want to add more nuance to the mystery, not remove mystery altogether.

Conclusion

Games, like narratives, must have a great ending. Even if the middle is mediocre, your audience will forgive if the ending is satisfying. But no matter how great the build up, no one will care if you don’t deliver a satisfying ending.

If you planted the seeds in the setup for how a philosophy might apply to real life decisions, now is the time for that teaching to pay off. Here at the end is when you reward those who were paying attention, and surprise those who didn’t. This is the big reveal.

The Real Weight of War

In our example there will be an unexpected but certain consequence if King Henry employs Sir John Falstaff’s strategy, according to the Netflix version of this story. As shown in the following scene I posted below, Falstaff will feel obligated to lead the decoy division which will be on the frontlines and have to take on the brunt of the French forces for the duration of the battle. This would almost certainly lead to the death of most of these men. And they won’t do so bravely and stand their ground unless their leader, in this case Falstaff, leads them into battle placing him at the riskiest part of an already highly risky battle.

Which results in the death of the king’s best friend and only fully trusted advisor, a very poignant and longstanding relationship as depicted in this edited sequence of scenes from the film, “The King.”

Reading a letter from the president to the parents of a fallen soldier can also bring real emotional weight to the consequences. Real names help. The death of one million people is a statistic. The death of one person is a tragedy.

Flow Charts

If you get any more elaborate than this, and especially if you go the choose-your-own-adventure route, I recommend using a flow chart. Here is one I created using a free webapp in combination with Photoshop.

For more on how to bring games into the classroom take a look at my political science megagame, my card game of political intrigue, or help me develop my card game about environmental sustainability. To receive an occasional update about games I’m publishing be sure to sign up for my newsletter.