Strategies for Dealing with Uncertainty

Transcript:

My name is Shaun McMillan, and this is the Best Class Ever.

When I was a high school game design teacher I together with my students created a world peace political science megagame in which 72 participants all roleplay as world leaders. We would divide them up into twenty different nation-states, each with one to three leadership roles including the Prime Minister, the Secretary of Defense, or the National Scientist. We used a combination of huge war room game maps, board game components, poker chips, and tabletop RPG mechanics to let them negotiate, trade, make speeches, conduct black market illegal trade deals, or go to war. Each nation has different conflicting agendas and we give them four hours to solve all of the world’s problems. You can see the game for yourself if you visit the website, www.BestClassEver.org.

So as you can imagine, in order to design this we had to think a lot about systems, economics, and behavioral psychology. And as an artist trying to make a career in the industry I also thought a lot about creativity and the commercial world. It’s really hard to be successful by the world’s standards because there is so much competition if you want to do anything glorious.

Who hasn’t passed time thinking about what it would take to be successful on YouTube or tried to figure out a way to make money through some side hustle? But when it comes to actually doing creative work, very few people actually commit to building a career alternative. And the reason, I think, is because there are just too many variables to consider. work could I produce? Is there a market for my particular niche? How would I compete with others? Would I be successful? How do I even define success? How many followers is enough to consider myself a success? Isn’t it vain of me to want attention from others? Am I good enough? Would I make enough money?

Is my fate up to my own hard work and skill? How much of it is luck? This is the fundamental question every self-employed person has to consider. And its roots go all the way down to philosophy. What attitude should you take towards yourself, your fate, and that of your competition? How should I treat my enemies? How much do I not know? What will determine my fate? How do we deal with uncertainty?

I would like to explore some interesting strategies in dealing with these difficult questions. It will take more than one lesson, so I believe it is a subject I will be able to return to time and time again. But for today, let’s talk specifically about Prisoner’s Dilemma.

Prisoner’s Dilemma – Mathematicians and business majors are exploring political science theory and philosophy through game theory. Game theory is a college level math class that is typically attended by math majors and business majors. Why business majors? Because game theory is the study of how to use logic to find the optimal strategy in a competitive situation. And the most common simulation to come out of game theory is the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Here is the scenario.

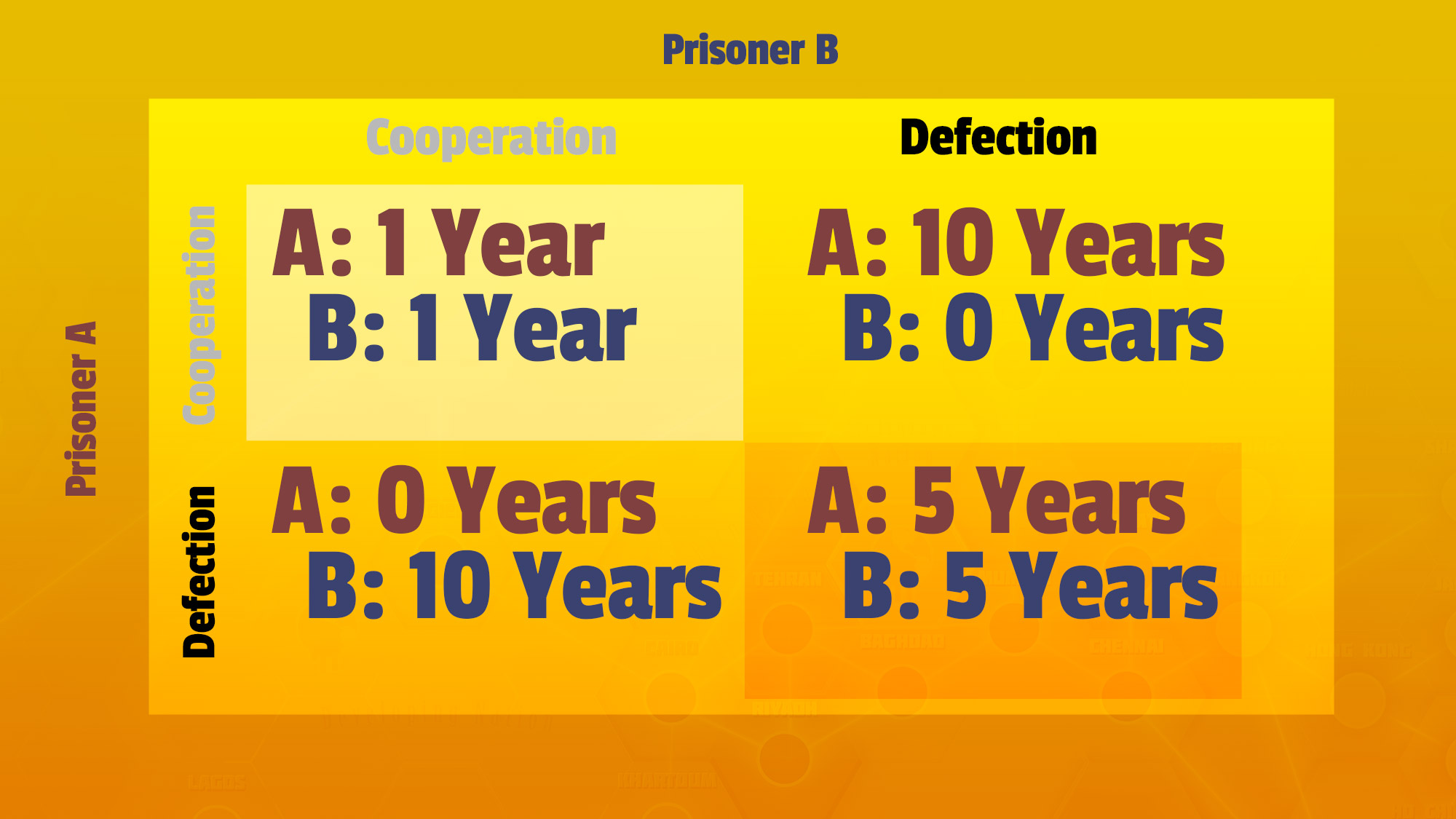

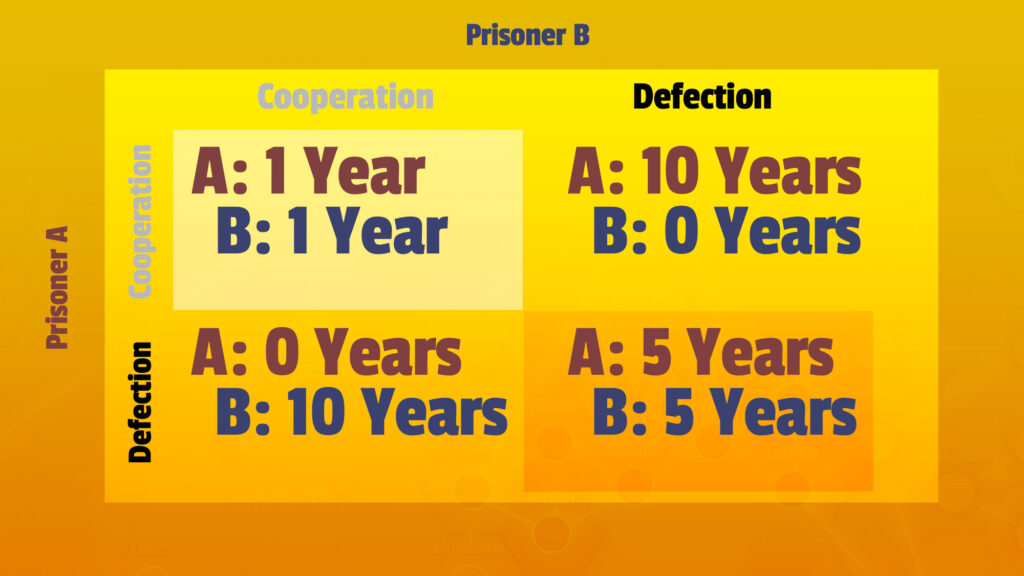

Think that you and a stranger are recruited to rob a bank. But before you rob the bank together you are both arrested. You are separated and placed into separate interrogation rooms. The police present each of you with the same offer. If both you and your partner remain silent according to the criminal code of never ratting on your partner and you both refuse to confess then the police will give you both 1 year in prison because they caught you at the scene ready to commit the crime. But this is not what the police want. They want to assign a total of 10 years prison time. So they offer you each another set of alternatives. If your partner refuses to confess but you agree to rat him out, then we’ll give him 10 years prison time and you can go free. But if he confesses and rats you out while you try to hold out refusing to confess, then you will get the 10 year prison sentence and he will go free. If you both confess to the crime then you both get 5 years prison time.

What would you choose? Stay true to the criminal code and never confess (cooperate) or confess your crimes and rat the other guy out (defect)?

In game theory we use simple sets of quadrants to plot out all of the alternative scenarios that result from your combination of choices. To see what this looks like simply visit www.BestClassEver.org

In prisoner’s dilemma there are two actors each making a choice with two options. That means we have a total of four alternative outcomes.

Prisoner A, that’s you, can collaborate, which in this scenario means to hold out according to the thief’s honor. Or you can defect, which in this scenario means to confess and rat out the other guy. Prisoner B has this choice to make.

To reason out what your most rational choice is, simply compare the two outcomes of your collaborative option. And compare those two outcomes with the two outcomes should you choose to defect. If you hold out in hopes that your partner will also hold out, you will either get 1 year in prison or 10. If you defect, then you will either get 0 years in prison, or 5 years in prison. Which sounds like the more rational choice?

And remember, you don’t really know the other guy, so you can only really assume that he also will make the rational choice. This is why we call it prisoner’s dilemma. It is a game that is systematically designed to incentivize bad behavior.

It’s easy to see this as rational if you are only going to play the game once. It might feel a little immoral to discard the interests of your opponent, but it’s not like you’ll have to face him again. But what if you had to play the game repeatedly against the same opponent? Not just once, not just twice, but repeatedly again and again and again? What if each of you was keeping a record of how he played against you in the past? Is it still rational to defect? Is it now rational to collaborate? How many times should you let him burn you before you hurt him back? Should you sell him out early on? Later on? Should you be forgiving? How forgiving?

Political Science

This isn’t just a hypothetical situation. Think about the Cold war in which President Kennedy and Russian President Khrushchev were in a nuclear showdown in which neither wanted to escalate into full nuclear fallout, but didn’t want to be the only one backing down and thus making themself and their nation look weak. As it turns out, humiliation is a very strong motivating factor. We just nearly came to the brink of mutual fallout during the Cuban missile crisis.

The Rules to Rule in the Battle of the Philosophies

At the time many political scientists were publishing theories about how to resolve this prisoner’s dilemma. The fate of the earth was at stake, but it was all just theory. That was until in the early 60s when Robert Axelrod held a computer programming competition. He posted an ad in a computer programming magazine inviting anyone with a theory on how to resolve prisoner’s dilemma to program their solution into a set of code that could be played against every other participant’s code.

Each submission was a simple set of rules that said what to do in the first game, and how to respond in each subsequent game. Each was also given a name. So for instance a simple one was called, “Satan.” It’s rules were simple, it always chose to defect from the first game on.

Another one called “retaliatory strike,” had a set of rules that said to collaborate in the first game and every subsequent game so long as the opponent also collaborated. But as soon as the opponent defected, retaliatory strike would defect every game from then on.

If these two programs played against each other then retaliatory strike would lose the first game, and then both would defect on into infinity.

If Satan played against a program that always collaborated no matter what then Satan would take advantage each and every time. But if retaliatory strike played against the same optimistic program then they would both collaborate again and again on into the future.

Some of the programs had very simple sets of rules, maybe only two or three lines of code, and some were extremely sophisticated using a lot of code.

He then played each set of code against every other set of code multiple times to see which produced the best results on average against all the other programs.

Tit for Tat

To his surprise there was one program that fared really well against nearly every program. It had a surprisingly simple set of three lines of code. This program was called, “Tit for Tat.” Initially it would always collaborate on the first round. Then in the second round it would simply do what it’s opponent did the round before. If the opponent collaborated, then it collaborated. If the opponent defected, Tit for Tat also defected. If the opponent changed course, then Tit for Tat immediately changed course the very next round. This made it extremely versatile, and extremely forgiving.

Against both Optimist and Retaliatory Strike it would collaborate on into infinity. But against a more aggressive program like Satan it would not lose more than the first game.

God treats according to what they have done

So what can we learn from this strategy? I would argue that it very closely resembles God’s strategy in Romans 2:8 and Proverbs 24:12,

“God ‘will repay each person according to what they have done.’”

-Romans 2:8 and Proverbs 24:12

Some parallels can also be drawn to elements of Christian philosophy. While Tit for Tat will certainly return fire for fire, it is quick to forgive and does not hold a grudge. It’s important to remember that while Jesus was known for his love and mercy, his philosophy did have two sides to it. He said,

“I am sending you out like sheep among wolves. Therefore be as shrewd as snakes and as innocent as doves.”

-Matthew 10:16

And Jesus’ patience may not have been infinite, but it was certainly extensive enough to challenge the standards of his disciples.

Then Peter came to Jesus and asked, “Lord, how many times shall I forgive my brother or sister who sins against me? Up to seven times?”

Jesus answered, “I tell you, not seven times, but seventy times seven times.

-Matthew 18:21, 22

Parents are often quick to scold their children for cheating, but when asked why we usually respond with some sort of cliche about sportsmanship. Why not cheat? If you are only going to play once then cheating clearly presents itself as a rational choice. The problem is we don’t just want to win the game. We need to win the game in a way that doesn’t get us kicked out of future games. This is where morality emerges. How can we play the game of life in a way that leads to me winning and those closest to me winning the most often over the longest course of time?

If you want to do something meaningful, or build something that will last longer than yourself. If you want to benefit others and leave a good legacy for your children, your community, or make history then it is in your own best interest to employ ethical strategies that sacrifice short term gain for long term sustainability.

The Utility of Morality & Ethics

Though game theory has led to some interesting finds, it still doesn’t solve the problem of uncertainty. Especially when we consider the fact that game theory assumes the players will act rationally in their own best interest. But if we know anything about human beings, it is that they often act irrationally, and are even willing to sabotage their own situation in order to pursue irrational emotional impulses. But at least game theory shows us yet another argument for the utility of morality and ethics. And remember the key points of the Tit for Tat’s winning strategy

- Begin with trust and continue to trust even strangers until they give you a reason not to.

- Treat wickedness with an equal and appropriate response.

- Be quick to forgive and allow for people to change.

Next Lesson

But even if we can reason this out in a rational way, it is still daunting to start something new in such a competitive market where the majority of new businesses fail before they can reach a sustainable scale. So to achieve long-term success we still need to find strategies for dealing with short term uncertainty. And to do this we will have to look more deeply at daily life practices. So join me in our next lesson where I will explore some healthy life hacks.

As always, if you would like a transcript of today’s lesson, or would like to subscribe to the podcast, please visit www.BestClassEver.org.